Other than the complaint of dyspnea and/or chronic cough, the depressed patient often presents few recognizable symptoms. If the patient is anxious, the physician may note palpitations, tachycardia, dyspnea, sweating, or a general sense of unease or impending doom. When depression and anxiety coexist, the physician is immediately alerted to the anxiety and may fail to recognize the depression. When anxiety masks depression and the anxiety alone is treated, depression may increase. For example, when a patient presents clear symptoms of what appears to be anxiety, one of the benzodiazepines, such as diazepam (Valium), may be introduced. However, the depressive qualities of diazepam may exacerbate the depression.

Other than the complaint of dyspnea and/or chronic cough, the depressed patient often presents few recognizable symptoms. If the patient is anxious, the physician may note palpitations, tachycardia, dyspnea, sweating, or a general sense of unease or impending doom. When depression and anxiety coexist, the physician is immediately alerted to the anxiety and may fail to recognize the depression. When anxiety masks depression and the anxiety alone is treated, depression may increase. For example, when a patient presents clear symptoms of what appears to be anxiety, one of the benzodiazepines, such as diazepam (Valium), may be introduced. However, the depressive qualities of diazepam may exacerbate the depression.

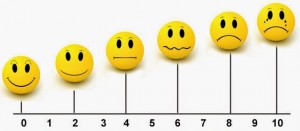

Although the general physician should not attempt psychotherapy with either extremely anxious or depressed patients, he can do much to alleviate their suffering. Empathy is one of the most important concepts to understand and to be able to convey to the suffering patient. A common feeling of these patients is that no one feels as anxious or as depressed as they do. The conclusion then is that no one understands them or how they feel. Although treating these patients with disdain, scorn, or discrimination is psychologically harmful to them, telling a depressed patient to “cheer up” can be equally devastating. The COPD patients might be depressed over the loss of a job, physical functioning and activity, or loved ones. These losses are real, not imagined, and to insist that the patient “put on a happy face” is to deny that his doctor understands and cares for him. Reassurance and hope can be extremely helpful, but the extent of his problems should not be denied or minimized.

Some of the more common signs of depression in COPD patients are insomnia, decreased appetite, social withdrawal, indecisiveness, a sense of failure or disappointment in self, sadness, difficulty in concentration, dyspnea, suicidal ideation, lethargy, helplessness, and hopelessness. Decreased energy levels, despondency, and lack of interest in life may also be indicative of treatable with remedies of Canadian Health&Care Mall depression.

The Beck Depression Inventory, Short Form can be used in family practice to screen depressed  patients. The test requires five minutes to administer and consists of 13 items. A self-rating depression scale (SDS), which consists of 20 statements relating to a specific, common characteristic of depression, has been published. The patient merely checks the items most applicable to him at the time of the test. Scoring is simple.

patients. The test requires five minutes to administer and consists of 13 items. A self-rating depression scale (SDS), which consists of 20 statements relating to a specific, common characteristic of depression, has been published. The patient merely checks the items most applicable to him at the time of the test. Scoring is simple.

Perhaps the most generally accepted psychodynamic explanation of depression is the experience of loss. For the COPD patient, the losses increase as the disease progresses. The patient may first have to curtail his more active recreational interests and may then eventually lose his job or be forced to modify it. Relationships may suffer and deteriorate as the patient becomes less able to participate in normal daily activities. Some patients become reluctant to socialize because of embarrassment over cough and sputum production, and others avoid sexual contact because of fear of dyspnea and fatigue. For those patients who set high standards for themselves, reluctance to accept compromises in employment, recreational interests, and interpersonal relationships may lead to frustration and depression.

The treatment of depression involves helping the patient face his feelings of fear, anger, and sadness over his limitations and losses. Openly telling him that you know and understand that such feelings are not an uncommon reaction to his illness may relieve the patient from feeling misunderstood and alone. Once his various emotional reactions have surfaced, and are recognized, acknowledged, and discussed, problem solving becomes more feasible. In this way, the patient learns to accept that these matters, in addition to his respiratory symptoms, must be handled or treated with Canadian Health&Care Mall’s medications.

If depression has not already takeif its toll on the patient’s sexual interest, perceived lack of control over episodes of dyspnea may limit his sexual activity. One of the common fears voiced by both male and female patients is that they never know when they might become too tired or dyspneic during intercourse to continue. Some patients have found that the only way they can participate in a sexual  relationship is soon after bronchodilator medication, midday, and with the patient in the passive position. For some men, the switch to the passive position, and for some women, the change to an assertive position can often prove unsettling. Marital counseling may be necessary in some cases. Kass et al have observed that some individuals whose sexual problems were associated with COPD might well have had the same problems if they had never had COPD. Some patients, however, had better sexual relationships because the partners involved were willing to make needed adjustments.

relationship is soon after bronchodilator medication, midday, and with the patient in the passive position. For some men, the switch to the passive position, and for some women, the change to an assertive position can often prove unsettling. Marital counseling may be necessary in some cases. Kass et al have observed that some individuals whose sexual problems were associated with COPD might well have had the same problems if they had never had COPD. Some patients, however, had better sexual relationships because the partners involved were willing to make needed adjustments.

In the later stages of the disease, or following a severe acute exacerbation, some COPD patients may focus their attention on dying and may even fantasize about the circumstances of their death and its impact on others. This fantasizing may either create problems or may serve to encourage the patient to make some necessary decisions. For example, a patient may fear leaving the hospital or ever attempting to live independently. On the other hand, a patient’s death fantasies may spur him on to reexamining his life’s priorities and acting on them, instead of continually focusing on the regret of the past and worry of the future.

The patient and his family should be made aware of the realities of his illness. It is usually insufficient for the patient to express his views on dying and go on to other matters. Despite being severely handicapped, he may be kept alive by his hope. This hope could be destroyed by bringing the prospect of death to his attention without appropriate emotional support. Recently in the literature, more attention has been given to the needs of the dying patient. Kubler-Ross has outlined the stages of the dying patient and emphasized the need of many terminal patients to discuss their feelings about death. We have emphasized the need for an understanding, empathic physician-patient relationship, and at no time is this more important than when the patient is coming to terms with dying.

Patients who have considerable physical dysfunction, have lost their jobs, or have serious disruptions in family life, should be evaluated for suicidal potential. If the patient manifests depressive symptoms, the physician may ask how he intends to cope with these feelings. The response may reveal suicidal tendencies. Directly asking the patient whether he has thought of suicide may sometimes bring the problem into the open. Referral to an appropriately trained mental health professional is indicated if the physician notes signs of severe depression.

chronic cough, COPD, emotional reactions, hyperactive body, lung damage